By Jeffrey Mansfield

Trevor with his wife and daughter, Rhinedd

“If the right to life is the first of all human rights, being the one on which all other rights depend, the right to refuse to kill must be the second.”

– Memorial stone to Conscientious Objectors

Temple of Peace, Cardiff

If you were asked to name the people and places associated with the search for peace during the 1930s, you probably wouldn’t mention William Trevor Jones of Pontyberem.

Yet some of the most important players in the peace movement were all guests at the Pontyberem home of William Trevor Jones – coal-miner, Christian, Labour Party activist and conscientious objector (CO) in the Second World War.

George Lansbury, Clement Attlee, Scott Nearing, and Canadian journalist Douglas Carr, all visited Trevor, as he was known.

With kind help from Rhinedd Rees, Trevor’s daughter, and her husband Alban we are able to reveal the hidden history of Trevor’s life and his experiences as a C/O. It is a cameo of industrial south Wales at the time.

Trevor then (left), daughter Rhinedd now, with husband Alban (right)

Early life

A coal-miner at age 14, he joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in 1918 after hearing an election speech by local Labour candidate, Dr. Williams. Asked to set up a branch of the ILP, he recruited four other colliers, and was elected Secretary.

He resumed his education by taking adult education classes and almost gained a scholarship to Oxford, failing by only one mark. During 1926 he supported the General Strike and acted as Secretary to the Children’s Distress Committee. When his ILP branch decided to join the (new) Labour Party in 1928, he was elected to Pontyberem Parish Council, on which he served until 1969.

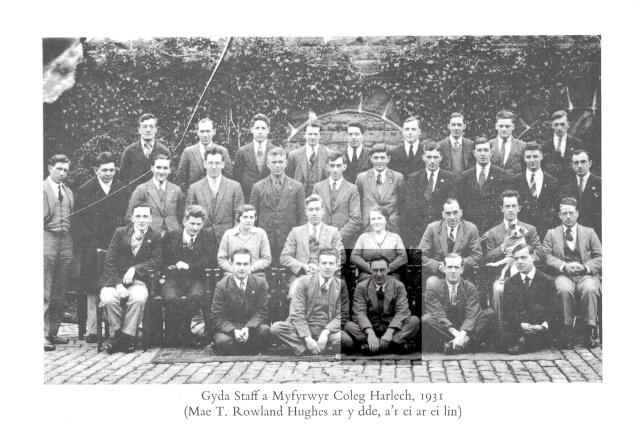

In 1930 he attended Coleg Harlech to continue his education but had to leave after one year and return to Pontyberem after his father was killed in the colliery. He later said that his time at Coleg Harlech had been a great influence on him and made him more capable of service to society.

Trevor at Coleg Harlech, highlighted in the bottom row

Between 1934 and 1935, Trevor’s Labour group were active in promoting the Peace Ballot in their region, and he began serving as Trades and Labour Council Secretary.

Though he came from an Anglican family he did not approve of what he felt was a militarist stance by the Church, and on marriage he became a Welsh Independent.

War breaks out

At the outbreak of World War Two in September 1939 Trevor was employed as an Insurance Inspector with the Co-op Insurance Group.

The National Service (Armed Forces) Act was passed into law, requiring all males aged between 18 and 41 to register for military service. Registration was by age group and took a long time, so it wasn’t until June 1941 that 40-year-olds were registering. Trevor’s 40th birthday was on 17th May 1941 – his time to register was imminent.

However, as a committed Christian, he decided to apply to register as a Conscientious Objector (CO) on religious grounds.

The application

His application was received at the Ministry of Labour and National Service in Cardiff on 13th June 1941, just one day before the deadline. The original papers pertaining to his application, kindly provided by Rhinedd, give a fascinating insight into the process.

He begins with a statement of his Christian values:

“As a professed Christian and a humanitarian, I profoundly and conscientiously believe that War, in all its aspects, is in direct contradiction to the Life and Teaching of Jesus Christ.”

He states his conviction that only by following Jesus can Man be liberated:

“The salvation of mankind does not lie in the way of force.”

Finally, he claims his moral right to the dictates of his own conscience and stands:

“On the firm conviction that to me each man is a potential Christ.”

The hearing

His application was heard by the Local Tribunal in Carmarthen on 18th July 1941. We have no record of what was said, but it is known that these hearings could be hostile and often tried to persuade, guide or command the applicants into some form of service.

Interviewed in 1972, Trevor said he was expected to leave his job with the insurance company and go back to the mine. Mining was a ‘reserved occupation’ and miners of his age were exempt from conscription, but he refused to do so because he didn’t believe it was right for him to take another collier’s job, which would have subsequently meant that collier having to join the army instead.

The application was granted and he was registered unconditionally in the Register of Conscientious Objectors, effective 23 July 1941. He said in 1972 that he felt he had ‘got off lightly’ in front of Judge Frank Davies at Caerfyrddin.

Aftermath

Like other COs he encountered rejection. Rhinedd recounts that some people spat on him, and threw stones on the roof when he was addressing meetings. But despite undercurrents of hostility, he had support in his chapel, where there were other COs, and he was elected Deacon. He continued working with the Insurance, which he could not have done had he been shunned. He was even asked to provide references, evidence that he was recognised as a man of conscience.

But the whole experience took its toll: after the war he became less confident and suffered a nervous breakdown, giving up his job as Inspector to become an ordinary Agent.

Trevor in his later years

Final thoughts

The coalfields, the Independent Labour Party, and the religious faith which nurtured Trevor have now either disappeared or are less visible in society. But the courage which he and other COs showed is everlasting and serves as an example to us all.

“Mae Alban, Catrin, Anwen a finnau yn ymfalchio yn fawr ar ei safiad a’i ddewrder ar gyfnod anodd iawn. Roedd yn berson egwyddorol ac roedd yn barod i wrthwynebu anghyfiawnder a chasineb yn erbyn cyd-ddyn.Bu’n driw i’w ddaliadau trwy gydol ei oes.”

-Rhinedd Rees, Hydref 2017

“Alban, Catrin, Anwen and I are very proud of the stand he made and his bravery during a very difficult period. He was a very principled person and was ready to oppose injustice and hatred against his fellow man. He was true to his beliefs throughout his life.”

-Rhinedd Rees, October 2017

Thank you to Rhinedd for your involvement with this piece and the family photographs.