Visit and search Wales’ Book of Remembrance online at www.BookofRemembrance.Wales / www.LlyfryCofio.Cymru

Wales’ Temple of Peace and Health, home of the Welsh Centre for International Affairs and the HLF-funded ‘Wales for Peace’ project, was built as the nation’s memorial to the fallen of World War One – a memorial that would inspire future generations to learn from the conflicts of the past, to chart Wales’ role in the world, and to work towards peace.

100 years ago this weekend, the world said ‘Never Again’ to conflict, as the Armistice Bells tolled on 4 years that had wiped out a generation. A nation in agony of grief and mourning braced to rebuild, and to build a better world.

100 years later, the red poppies of military remembrance – as well as the white poppies for peace, black poppies for BME communities, and purple poppies for animals lost in war – all mark the minute’s silence at 11am on 11.11, poppies for people of all perspectives.

But on #WW100, our poppies of all colours also remember those who have fallen and been left behind by a century of conflicts since – WW2, Spain, Korea, Colonial Wars, the Cold War, Vietnam, Falklands, Gulf, Balkans, War on Terror, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria… What has the world really learned from Remembrance? To glorify war… or to prevent it?

The Davies Family of Llandinam

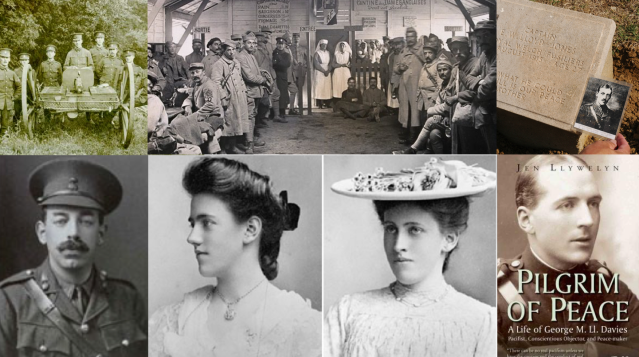

Differing attitudes to confronting conflict are not new. Through WW1, the Davies family of Llandinam in Powys would have had dinner table debates that represented the cross-section of society. Grandchildren of the Welsh industrialist David Davies:

- David Davies (Jnr) (later Lord Davies of Llandinam) was a soldier in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, and Parliamentary Private Secretary to war leader David Lloyd George. But he was horrified by the carnage he witnessed on the Front, and he dedicated his life to pursuing peace – including founding the first Dept of International Relations in the world in Aberystwyth (celebrating their centenary in 2019), and Wales’ Temple of Peace and Health (celebrating #Temple80, our 80th anniversary, in Nov 2018).

- Cousin Edward Lloyd Jones reluctantly signed up to a war he saw as unjust; but was killed in Gallipoli, aged just 27.

- Cousin George M Ll Davies was a Conscientious Objector, who was imprisoned in Wormwood Scrubs for refusing to take up arms – but after WW1, was elected as a Member of Parliament for the University of Wales, and became one of Wales’ most renowned peace builders – known as ‘the Pilgrim of Peace’.

- Gwendoline and Margaret (Daisy) Davies, horrified by the war, joined the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry to run a canteen in Troyes, France where they supported soldiers going to and from the Front. Devastated by their cousins’ death, they supported George as a CO. After WW1 they set up the Gregynog Press, supported creation of the Book of Remembrance, and helped set up the WEAC (Welsh Education Advisory Committee) which produced the world’s first Peace Education Curriculum, and became a blueprint for UNESCO.

Creation of the Book of Remembrance

In the early 1920s, as families grappled with the Aftermath of WW1 and their loss, memorials sprang up Wales-wide. A Welsh National War Memorial was proposed for Alexandra Gardens in Cathays Park. The 35-40,000 names of Wales’ fallen were to be inscribed in a beautiful Book – Wales’ WW1 Book of Remembrance – that would become a work of art, a national treasure and a place of pilgrimage.

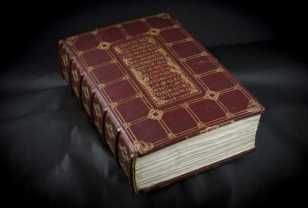

The Book is the work of world-renowned calligrapher Graily Hewitt, working closely it is thought with the Davies sisters and their Gregynog Press artists. A great nationwide effort was made to gather the names of the fallen; and a team of women in Midhurst, Sussex worked over several years to complete the Book.

The Davies sisters and the Gregynog Press had a mission to create books of high art and beauty. Bound in Moroccan Leather, with Indian Ink and Gold Leaf on pages of Vellum, the fine illumination techniques were a revival of Mediaeval skills.

View Flickr Album of the Book of Remembrance in the Temple of Peace

“this Book of Souls, reposed upon a stone of French Marble, encased in Belgian Bronze, illuminated individually, painstakingly by hand in Indian Ink and the finest Gold Leaf upon handcrafted Vellum… bound in a volume of Moroccan Leather, entombed in a sanctuary of Portland Stone and Greek collonades. It seemed as if the whole Empire were as one in the creation of this memorial to those whose loss must live forever.”

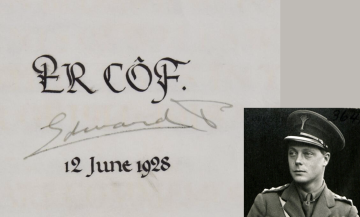

The 1,205 pages of 35,000 names were completed in March 1928; and the Book was signed, on 12 June 1928, by Edward Prince of Wales – the future King Edward VIII – on a page emblazoned ‘Er Cof’ – In Memory. It was formally unveiled to the public on 11.11, 1928 – the 10th Anniversary of the Armistice – at the opening of Wales’ National War Memorial in Alexandra Gardens, Cardiff. For the first decade, the Book was held at the National Museum of Wales. But its creation had inspired a greater mission.

Wales’ Peacebuilding movements had been particularly active through the 1920s on the international stage. Lord David Davies had a vision that Wales should lead the world in the realisation of Peace, enshrined in bricks and mortar – by building the first in what was hoped would be a string of ‘Temple’s of Peace’ around the world.

A Temple of Peace

Leading architects were invited to design a building that would both hold the Book of Remembrance, and inspire future generations – and in 1929, Cardiff architect Percy Thomas was commissioned to design Wales’ Temple of Peace, on land given by Cardiff Corporation. After a slow start during the Great Depression, in 1934 Lord Davies gave £60,000 of his own money to get the project off the ground.

In April 1937, the Foundation Stone was laid to great ceremony in Cathays Park, Cardiff, by Lord Halifax – one of the leading ‘peace politicians’ of the time. But the late 1930s were troubled times; the post-WW1 ‘Peace Reparations’ that had crippled Germany, had led Hitler to power – and Lord Halifax, working hard to avoid war at all costs, would go down in history as an ‘appeaser’ (although this is a perhaps unfair and simplistic view of his peace building attempts). But even as the Temple was under construction, sandbags and bomb shelters were being constructed on the streets either side.

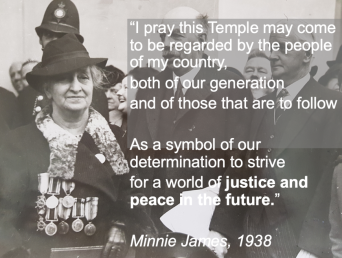

“A New Mecca – the Opening of Wales’ Temple of Peace and Health” Blog Piece by Dr. Emma West for the ‘Being Human Festival’.

In Nov 1938, the Temple of Peace was opened by ‘Mother of Wales’ Minnie James from Dowlais, Merthyr Tydfil, who had lost 3 sons in WW1 – representing the bereaved mothers of Wales. She was accompanied by representatives of mothers from across Britain and the Empire, identified through the British Legion and local Press campaigns. The Temple sought to champion equality from the outset – although the opening ceremony was very much ‘of its time’, as the women were not able to write their own speeches.

The inclement weather of the opening day, and the umbrellas of the massive crowds assembled to watch, were a poignant reminder that storm clouds loomed over Europe. It would be only months later that WW2 finally broke out.

View Video of Press Cuttings from the 1938 Opening of Wales’ Temple of Peace

“We will Remember Them” by BBC’s Huw Edwards, Nov 2018, features 3 minutes on the Temple of Peace and Book of Remembrance (from 38.30)

A Place of Pilgrimage

Despite the outbreak of war, the Temple of Peace became a place of pilgrimage for people from all over Wales. In an era when travelling to France, Belgium or even further afield was beyond the reach of most working people, community groups and schools Wales-wide would organise ‘pilgrimages’ to visit the Book of Remembrance. These visits were often promoted extensively in local newspapers.

The Crypt in 1938

The Crypt in 1938

At 11am every morning, a page of the Book would be turned – the names announced in the press the week beforehand, so that relatives could come to witness the ceremony as their loved ones were spotlighted. Visitors would take part in a beautiful, solemn yet forward looking Service of Remembrance, compiled by the Davies Sisters of Gregynog – and would sign a visitors book pledging their allegiance to pursuit of peace.

After WW2 another generation of Welsh men and women had fallen; and a WW2 Book of Remembrance was commissioned. Though intended to reside alongside the WW1 Book, for reasons lost to history it has remained hidden from view and access within the archives of the National Museum of Wales. As recent as 1993, architectural plans were drawn up to adapt the Hall of the Temple of Peace to display both books side by side. But to date, they have never been united, and this remains an aspiration of the Welsh Centre for International Affairs (WCIA) to this day.

As the survivors of the WW1 generation grew older – and as overseas travel has become easier – visitors to the Book of Remembrance grew lesser over the years. The Book, and the Temple, has been visited by such luminaries as Peres de Cuellar, Secretary General of the United Nations, in 1984; and Desmond Tutu in 2012. But by 2014, it seemed the Book of Remembrance had been largely… forgotten?

Remembering for Peace – 2014-18

In 2014, WCIA alongside 10 national partners developed the ‘Wales for Peace’ project, funded by HLF and supported by Cymru’s Cofio / Wales Remembers, which aimed to mark the centenary of WW1 by exploring one big question:

“How, in the 100 years since WW1, had the people of Wales contributed to the search for peace?”

As guardians of the Temple of Peace, WCIA’s project started with making the Book of Remembrance accessible again to the public. The aim was to create a travelling exhibition – uniting the Book for the first time with the communities Wales-wide from whom its 35,000 names originated; and to digitise the book, so it could be accessible online to future generations.

Transcription of the book was launched on Remembrance Day 2015 with an event at the Senedd, Cardiff Bay, where Assembly Members were invited to view the book and transcribe the first names. A nationwide call was launched for volunteers, schools and community groups to participate in a ‘Digital act of Remembrance’.

Local workshops, from Snowdonia to Swansea, enabled people to be part of ‘making history’. Schools developed ‘hidden histories’ projects discovering the stories behind the names, an experience that proved deeply moving for many as they connected to people long forgotten.

Exhibition Tour

The Remembering for Peace Exhibition was launched in the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth in January 2016. It has travelled onwards to:

- Bodelwyddan Castle, Denbighshire, including an event with Flintshire War Memorials

- Temple of Peace, Cardiff for #Somme100

- Caernarfon Castle, Gwynedd – alongside Poppies: Weeping Window and the Caernarfon Peace Trail

- Narberth Museum, Pembrokeshire

- Oriel Mon, Anglesey

- Senedd, Cardiff Bay – alongside Poppies: Weeping Window and Women War & Peace

- Swansea Museum, as part of the ‘Now the Hero’ Memorial Arts event

At each exhibition venue, local partners have worked with community groups to draw out diverse local stories, so every exhibition has been different. A Schools Curriculum Pack, ‘Remembering for Peace’ is available on Hwb, and a Hidden Histories Guide for Volunteer Groups has been widely used beyond the Wales for Peace project.

The Book of Remembrance Online

For Remembrance Day 2017, WCIA and the National Library of Wales were delighted to unveil the completed digital Book of Remembrance and search functionality online at www.BookofRemembrance.Wales / www.LlyfryCofio.cymru.

This is not only a hugely symbolic act of remembrance in itself, but a great credit to over 350 volunteers who contributed towards transcribing the Book to make it accessible for future generations. Their outstanding contribution was recognised when the National Library was bestowed the prestigious Archives Volunteering Award for 2016.

A curious discovery from the digitising process has been the question of ‘how many died’? Most history references – including about the creation of the Book of Remembrance – quote 35,000 as being the number of men and women of Wales who fell in WW1. But just under 40,000 names (39,917) emerged from the transcription data – which suggests Wales’ losses may have been even greater than previously thought.

Soldiers Stories

The undoubted power of the Book of Remembrance is that behind every beautifully illuminated, gilded name, lies a life story – from the famous, to the ordinary, to the comparatively unknown.

Hedd Wyn (Ellis Humphrey Evans), Welsh poet and peace icon, who died in Passchendaele just days before attaining the crown of the National Eisteddfod. His prize, forever known as the ‘Black Chair’ and his home farm, Yr Ysgwrn, now a place of pilgrimage in Snowdonia for people learning about WW1, Welsh culture and Peace building. His nephew, Gerald Williams, has kept the doors open and Hedd Wyn’s memory alive, and planted the last poppy at Caernarfon Castle for the opening of the 14-18NOW Weeping Window art work in October 2016.

Alfred Thomas from St David’s was serving in the Merchant Navy when his ship, the S S Memnon, was torpedoed. 100 years later, his granddaughter, Gwenno Watkin, was one of the National Library volunteers transcribing the Book of Remembrance when she suddenly came face to face with his name – and went on to discover more about his loss in WW1.

Alfred Thomas from St David’s was serving in the Merchant Navy when his ship, the S S Memnon, was torpedoed. 100 years later, his granddaughter, Gwenno Watkin, was one of the National Library volunteers transcribing the Book of Remembrance when she suddenly came face to face with his name – and went on to discover more about his loss in WW1.

Jean Roberts, Eva Davies, Margaret Evans and Jennie Williams were all nurses with the Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Corps, who died serving in the field hospitals of France and Belgium. The story of women, war and peace has traditionally been overlooked among ranks of male soldiers – but their stories inspired creation of the Women, War and Peace exhibition, and Women’s Archive Wales’ ‘Women of WW1’ project.

Jean Roberts, Eva Davies, Margaret Evans and Jennie Williams were all nurses with the Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Corps, who died serving in the field hospitals of France and Belgium. The story of women, war and peace has traditionally been overlooked among ranks of male soldiers – but their stories inspired creation of the Women, War and Peace exhibition, and Women’s Archive Wales’ ‘Women of WW1’ project.

The Beersheba Graves. Eli Lichtenstein is a volunteer in North Wales who grew up in Israel. He was astonished to realise that he recognised many names in the Book of Remembrance from growing up as a child, and discovered that many of the men who fell in the Battle of Beersheba, in former British Palestine, were Royal Welsh Fusiliers from the Llandudno & Bangor area. Read Eli’s Blog Story.

David Louis Clemetson served with the Pembroke Yeomanry, and is one of many Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Welsh people, as well as those across Britain’s former empire, who lost their lives in WW1. In 2018, for WW100 the Temple of Peace hosted a BME Remembrance Service where the Welsh Government for the first time recognised the sacrifices and losses of Wales’ BME communities in successive British wars.

David Louis Clemetson served with the Pembroke Yeomanry, and is one of many Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Welsh people, as well as those across Britain’s former empire, who lost their lives in WW1. In 2018, for WW100 the Temple of Peace hosted a BME Remembrance Service where the Welsh Government for the first time recognised the sacrifices and losses of Wales’ BME communities in successive British wars.

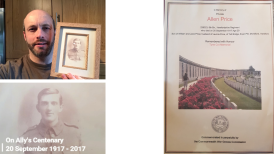

Everyone has a personal story; and Head of Wales for Peace Craig Owen was moved both to discover his own great grandfather, Ally Price’s story, and following a visit to his memorial in Tyne Cot, Belgium, created a short film for his family as he found out more about the ‘man behind the name’ from Radnor, Tredegar and Herefordshire.

Everyone has a personal story; and Head of Wales for Peace Craig Owen was moved both to discover his own great grandfather, Ally Price’s story, and following a visit to his memorial in Tyne Cot, Belgium, created a short film for his family as he found out more about the ‘man behind the name’ from Radnor, Tredegar and Herefordshire.

David James from Merthyr Tydfil, who worked in the drawing office at Dowlais Colliery, served with the Welsh Guards until he was killed in action in October 1916. His two brothers also died from WW1 war injuries, as well as two sisters from cholera. Their mother, Minnie James, was chosen to open Wales’ Temple of Peace & Health in Cardiff in 1938 in their memory.

Video – Minnie James opens the Temple of Peace in 1938.

For the WW100 Armistice weekend, the Temple of Peace remembers all those who fell in the ‘war that was to end war’ – and all those who survived, and gave their all to build peace in the years that followed. Their mission remains as relevant today as ever.

Listen to more:

- Audio on Soundcloud – ‘Thoughts in the Crypt’ by E. R. Eaton – verbatim recording from the Western Mail supplement of Nov 23 1938, read by Craig Owen..

- ‘Peace Podcast’ on Soundcloud – Recording of the WCIA Temple80 Lecture ‘The Story of the Book of Remembrance’ from 9th November 2018, with Craig Owen, Wales for Peace; Dafydd Tudur, National Library of Wales; and Jon Berry, Temple of Peace Artist in Residence.

Explore the Book of Remembrance for yourself: