By Craig Owen

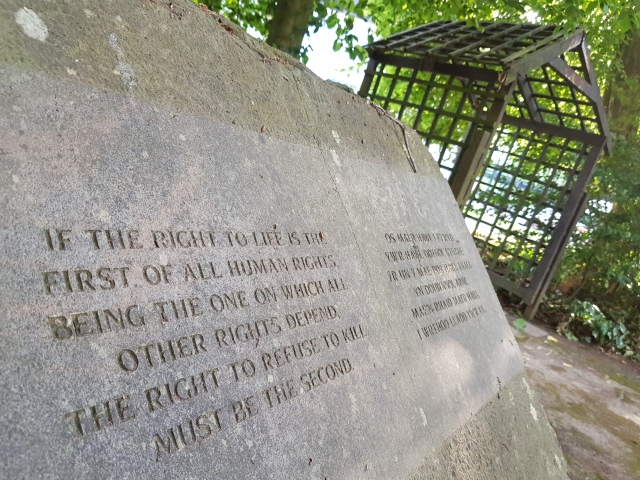

In Wales’ National Garden of Peace, between Cardiff’s Temple of Peace and the leafy grounds of Bute Park, stands an imposing stone unveiled in 2005 by peace campaigning group Cynefin y Werin, and dedicated to Wales’ Conscientious Objectors of all wars. Inscribed upon it is a challenge to all generations:

“If the right to life is the first of all human rights

Being the one on which all other rights depend

The right to refuse to kill must be the second.”

Conscientious Objectors Stone, Welsh National Garden of Peace. Craig Owen / WCIA

15 May every year has been recognised since 1985 as International Conscientious Objectors Day – remembering generations of individuals who have opposed conflict by refusing to bear arms.

Conscientious Objection is one of many ways in which generations of peace builders have put their ‘beliefs into action’ by opposing conflict. From the 930+ Welsh objectors imprisoned in WW1 for refusing to kill, to the anti-Nuclear campaigners of the 1960s-now, and ‘Stop the War’ protestors of recent years, Wales has a strong ‘peace heritage’ of speaking out against war.

–> Gain an overview from WCIA’s Opposing Conflict / Belief and Action pages.

–> To find out more about Wales’ WW1 Objectors, read our WCIA Voices May 2019 review of Dr Aled Eirug’s seminal book on ‘The Opposition to the Great War in Wales‘, published by University of Wales Press 2019.

Pearce Register of Conscientious Objectors

You can discover hidden histories of over 930 WW1 COs from communities Wales-wide, using the Pearce Register of Conscientious Objectors on WCIA’s Wales Peace Map.

WCIA are indebted to Prof Cyril Pearce of Leeds University for making his “life’s work” available to future researchers through our Belief & Action project.

Hidden Histories of Objectors

From 2014-18, Wales for Peace supported many volunteers, community groups and schools to explore ‘hidden histories’ of peace builders from WW1 to today. The following selection is a fitting tribute for this WW100 COs Memorial Day:

- Niclas y Glais, Swansea Valley (see digital story below) and George M Ll Davies of Llandinam, Powys by Noam Devey.

- Imprisonment to Parliament: Emrys Hughes of Tonypandy by Judith Newbold

- Who were Cardiff’s Objectors?; A Family Affair; Religion and Politics; and Mistreatment of Cardiff WW1 Objectors by Maggie Smales

- A Game of Cat and Mouse: Welshman Challenging the Military by Maggie Smales

- The Friends Ambulance Unit by Judith Newbold

- William Trevor Jones, Pontyberem, Carmarthenshire by Jeffrey Mansfield

- The Shepherds of Ystalyfera by Maggie Smales

- E.P.Jones of Pontypridd and Thomas Rhys and ‘Y Deyrnas’ of Bala Bangor, by Aled Eirug

- Albert Ruddall of Newport by Seren O’Brien

- Merfyn & Dyfnallt: World War Two Conscientious Objectors by Lion Wigley

View also some of the short films / digital stories created by young people working with Wales for Peace community projects over 2014-18, below.

‘Belief and Action’ Exhibition Tour

In 2016, WCIA worked with the Quakers in Wales and a steering group of Welsh experts to develop the ‘Belief and Action’ exhibition, which from 2016-19 has travelled to 15 communities Wales-wide and been visited by many thousands of people. Funded by Cymru’n Cofio / Wales Remembers and launched with an excellent community partnership event between WCIA and the United Reform Church in Pontypridd, the tour aimed to explore the stories and motivations of WW1 Conscientious Objectors, but with a key focus on reflecting on issues of Conscience ‘Then and Now’ during the WW100 centenary period.

–> View WCIA’s 2018 ‘Belief and Action’ Report

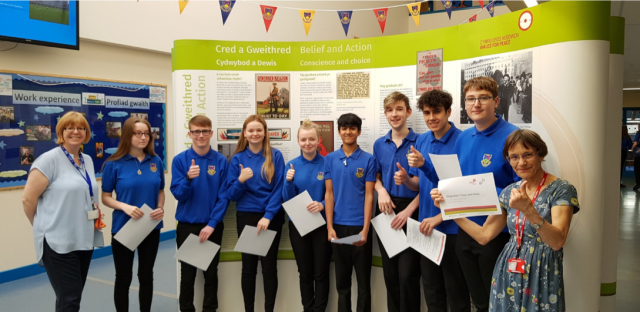

Young Peacemakers launch ‘Belief & Action’ at Ysgol Maesydderwen, May 2018

Last year, for 2018 Conscientious Objectors Day, Wales for Peace worked with Ysgol Maesydderwen in Swansea Valley to stage a Belief and Action exhibition, and also to launch WCIA’s Learning Pack ‘Standing up for your Beliefs’, downloadable from Hwb.

Learning Resources

WCIA, the National Library of Wales and Quakers / Friends in Wales have all produced substantial Curriculum Resources on Objection to War , including critical thinking materials and schools projects, available from the Welsh Government’s ‘Hwb’ Education Resources site for schools and teachers.

Find Out More / Take Action

- ‘Doves and Hawks’ BBC Wales Series by Aled Eirug on Soundcloud

- ‘The men who refused to Fight’: October 2018 feature by Martin Shipton and Aled Eirug

- Find out about Conscientious Objection today – Peace Pledge Union

- Quakers Conscience Action page

Short Films by Young Peacemakers

Over 2014-18, Wales for Peace was privileged to work with schools and community groups to explore hidden histories of peace with creative responses – including digital stories and short films

Short Film ‘Without the Scales’ by Merthyr Tydfil students of Coleg y Cymoedd / Uni of Glamorgan, with Cyfarthfa Castle Trust (displayed for Wales for Peace exhibition, Oct 2018), used records to re-enact the Conscientious Objectors Tribunals of WW1.

Short Film ‘Niclas y Glais’ by Ysgol Gyfun Llangynwyd, Bridgend (displayed for Pontypridd Belief and Action exhibition, Oct 2017) looked at the life of Thomas Even Niclas.

Digital Story ‘Conscientious Objectors’ by Crickhowell High School, Monmouthshire (displayed for Women War & Peace exhibition at the Senedd, August 2017) considered the feelings and experiences that led some WW1 soldiers to become objectors to war.